December 18, 2019 Industry news

Nick Brown, head of sustainability – Great Britain, at Coca-Cola European Partners Limited explained the company’s stance on recycling and deposit return schemes (DRSs) – where consumers receive money back for their empty drink containers at the point of recycling.

From Coke’s early soda fountains to successive generations of its iconic contour bottles, the company has a heritage of sustainable packaging.

In 1991, it began using recycled PET plastic in its packaging and constructed the UK’s first and only bottle-to-bottle reprocessing plant in 2012, which funds the collection of plastic bottles by local authorities.

In 2019, Coca-Cola switched the colour of its Sprite bottles from green to clear, making them easier to recycle into new bottles. In early 2020, the company is set to become the largest user of recycled PET plastic in Great Britain, with all of its plastic bottles comprising at least 50 per cent.

As well as the movements that Coke is making in its supply chain, the company is also increasing consumer awareness about recycling with a concerted marketing drive and community-based projects.

In 2017, they introduced smart Coca-Cola fountain dispensers, known as Freestyle machines, to the University of Reading campus.

The machines work with refillable containers that contain RFID tags. Students can buy soft drinks in reusable bottles, which Coca-Cola can then track by popularity and refill frequency. This system has reduced the packaging footprint for producers and consumers alike.

Coke’s “Round in Circles” campaign, launched in conjunction with Recycle Week 2019, seeks to highlight the circular journey that single-use plastics can take if they enter the recycling loop.

But Coca-Cola still realises there is a long way to go in a world where 500bn plastic bottles will be consumed every year by 2021.

What makes a good DRS?

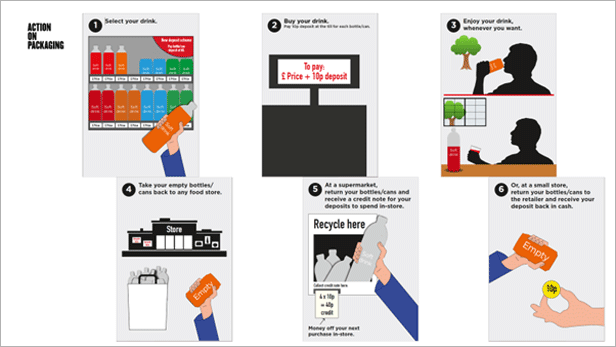

According to Brown, a functional DRS comprises the steps below, going from the purchase of a beverage to the potential of three different methods of reimbursement.

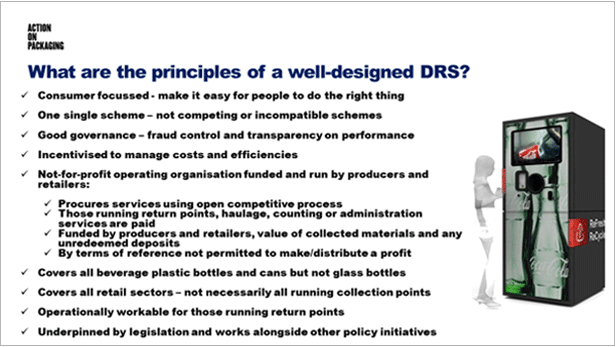

As far as the administration of the scheme, he underlined nine guiding values, based on experiences of existing DRSs on the European continent.

The current state of play in the UK with regards to the roll-out of DRS is a complicated one – with Scotland set to establish its own programme ahead of the rest of the UK. This has the potential to muddy the waters of an already complicated situation.

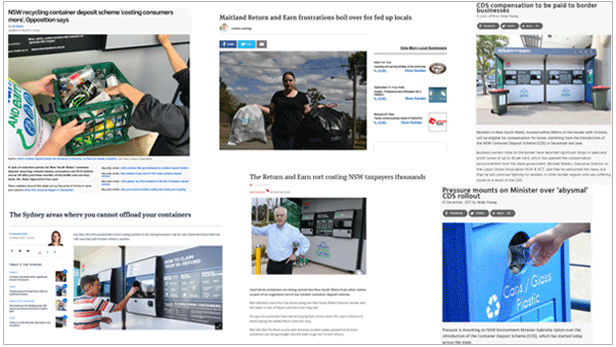

Fortunately, there is plenty of evidence of what not to do when setting up a DRS. In New South Wales, Australia, their “Return and Earn” scheme ran into problems, promoted by:

- Not being run by a single, not-for-profit organisation

- A lack of infrastructure in place at time of launch – only 6 per cent of the required return-points were up and running

- Machines unfit for purpose

- Commonplace defrauding of the system was – the scheme ended up compensating retailers up to 80km from state borders

The benefits of a well-run DRS are plain to see, with recycling rates in European countries that have DRSs in place topping the 90 per cent mark.

Learning from past successes and mistakes, industry should be able to come together and ensure policy makers understand the opportunities of a well-designed scheme, as well as the unintended consequences of a rushed one.